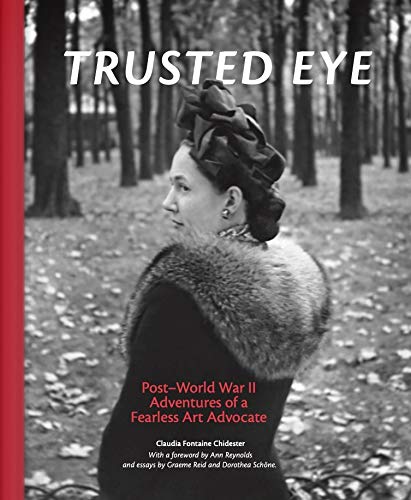

Trusted Eye: Post-World War II Adventures of a Fearless Art Advocate

by Claudia Fontaine Chidester, Fontaine Archive, 2021, 300 PP.

Hardback $37.99, ISBN: 978-0-9888358-2-5

A fascinating book, rich in archivalia, anecdotes, and insight, Trusted Eye documents the life and career of Virginia Fontaine (né Hammersmith, 1915-1991), “one of the most important promotors of art among the members of the American occupation forces” in immediate post-Second World War Germany.1 The art she promoted was modern art, especially German Expressionism and abstraction, both of which had been deemed “degenerate” in Nazi Germany and which she helped to reestablish in the western zone of occupation and, after 1949, the Federal Republic of Germany.

The author, Fontaine’s youngest daughter, was born in Frankfurt in 1956 and grew up in Germany and Mexico. In Austin, Texas she has created the Fontaine Archive documenting the life and work of her mother and father, the painter and graphic designer Paul Fontaine (1913-1996). Trusted Eye will be of great value to readers interested in three main themes: first, Women’s often underacknowledged, unappreciated and obstacle-filled roll in the creation and promotion of modern art; second, the art world of early twentieth-century Milwaukee which first formed Virginia Fontaine’s “trusted eye”; and third, most significantly, the postwar reconstructive period of German culture and specifically visual art—where Fontaine and the Fontaines formed an important link between the American occupying authorities, including “Monuments Men” and women, and German artists, art dealers, and museum professionals.

In addition to the main author’s extensive “warts and all” chronicle of Fontaine’s background, life and work (including Paul’s and Virginia’s foibles and infidelities, as well as Virginia’s alcoholism), the three main areas of interest receive enlightening discussions by noted scholars: the first by University of Texas at Austin art history professor Ann Reynolds, in her Forward, “Uneven Histories”; the second in the essay, “Wisconsin Art in the 1930s”, by Graeme Reid, director of collections at the Museum of Wisconsin Art; and the third by Dorothea Schöne, director of the Kunsthaus Dahlem Museum in Berlin.

Paul Hammersmith (1857-1937), a respected Milwaukee Realist artist—according to Reid “perhaps the most accomplished etcher in the city”—and founder at the turn of the century of the Hammersmith Engraving Company, supported his granddaughter’s artistic pursuits. Based on her studies at the Milwaukee Downer Seminary, the Layton School of Art, and Milwaukee-Downer College, Virginia was accepted into the Yale School of Art in 1935. It was at Yale that she met Paul Fontaine—who, unlike her, completed his Yale art degree. Her “Yale Fizzle,” as she and that chapter’s title put it, constituted one of the great disappointments of her career. Based on the solid quality of her artwork reproduced in the book, such as the 1939 Social Realist painting Flood (Milwaukee Art Museum), this “fizzle” is likely owed at least in part to systemic sexism.

After Paul’s graduation in 1940, the Fontaines married, and a scholarship he’d won took them to Tortola Virgin Islands for a year. They both pursued art projects during this time, Virginia’s involving unrealized book illustrations. From there, they moved to Paul’s hometown of Worcester, MA, until his induction into the army in 1943. While he served in the cartographic corps in Italy, back in Milwaukee Virginia learned the skill of exhibition organization at the Milwaukee Art Institute and under the mentorship of another woman, Polly Coan. After the war, Paul worked for the American military, first in Paris and then in Frankfurt, as a graphic designer. Virginia and their four-year-old daughter Carol joined him in the devastated Hessian city in August 1946. They remained in Germany until 1970 (in 1953 Paul became art director for the military newspaper, Stars and Stripes) when they decamped to retirement in Guadalajara Mexico, where Virginia died of emphysema in 1991 at age seventy-five.

In Frankfurt, Virginia became a friend and protege of the artist and art dealer Hanna Bekker von Rath. A gallery bearing Rath’s name still exists near Frankfurt’s central Römer square, exhibiting and selling the work of artists working in classic modernist formats and styles. The two women developed a symbiotic relationship—von Rath was well-connected in the German art world and presided over a capacious home with guest house. Fontaine had a car, access to gasoline and funds, an American passport, and connections among the occupiers that allowed her and them to travel around Germany visiting artists, collectors, and museum professionals, despite the official American anti-fraternization policy. In the narrative recounted by Chidester, several women travelling companions come to life: the judgmental but generous mentor von Rath; the cosmopolitan, but as Virginia complained, anti-Semitic, Zurich-based art dealer Chichio Haller, with whom she travelled to Paris and the Cote d’Azur; the statuesque Dutch dancer, choreographer and dance teacher Neeltje “Nel” Roos (1914-1970), with whom, according to the art historian Charlotte Weidler, Virginia Fontaine was “infatuated”; and the imperious American Brigadier general’s wife, Ansley Hill, with whom she drove her Volkswagen to Greece and Istanbul in 1962.2

Within the book’s main narrative of Fontaine’s life, the artists, mainly but not exclusively men, and their work come less to life than the women in Fontaine’s life. Male artists do feature prominently, though, in Fontaine’s own words, in two lengthy “reports,” on 1947 car trips to Berlin and with von Rath to Lake Constance (Bodensee) to visit artists and dealers. These previously unpublished single-spaced typescripts are reproduced as facsimile appendices. They make for fascinating reading, and for art historians of the period provide valuable first-hand reportage. She found the aging members of the pioneering Dresden Brücke (Bridge) German Expressionist group all hospitable but enervated—as she also deemed their recent work, in contrast to their pathbreaking pre-WWI paintings and woodcuts. She wrote, “today [Erich] Heckel is a very quiet man of 64, painting in his summer home on Bodensee,” but, comparing his placid landscapes of the current period with his audacious earlier work, she deemed them “realy [sic] awful” (222). Employing straightforward, midwestern, Hemingwayesque descriptors and and evaluations, she deemed Max Pechstein “a short gray-haired man, with blue eyes and a rudy [sic] complexion” (207). When the pioneering Expressionist showed her, at her request, some of his World War I-era work, she wrote: “This is what the world knew him best for and it was good, and strong; and also sad to see how little he been able to save” (207). Among the older generation of German artists, she rightly picked out the abstractionist Willi Baumeister (1889-1955), with whom the Fontaines became very friendly, as the leader and strongest painter.

In her Berlin and Lake Constance reports, Fontaine asserted that after the Nazis’ suppression of modern art, it would take another twenty-five years to develop younger German artists of international significance. This evaluation proved prescient. While a number artists, such as Joseph Beuys (1921-1986), the Baumeister student Charlotte Posenenske (1930-1985), Wolf Vostell (1932-1998), Gerhard Richter (b. 1932), and Hannah Darboven, (1941-2009) were developing important bodies of work in the 1950s and 1960s, contemporary German art would indeed not break through to international renown until the 1970s and especially the 1980s, when it rose to remarkable international prominence. Fontaine’s activities can thus be considered foundational to German art’s recovery and rise. As such, this book is a valuable resource for any historical inquiry concerning postwar German art.

1 Dorothea Schöne, “A Silent Sponsor: Virginia Fontaine’s Commitiment to Postwar German Art,” The Trusted Eye, p. 181.

2 “Her friend Charlotte Weidler noted, upon hearing Virginia’senthusiastic descriptions of Nel, that she was indeed infatuated. To which Virginia replied: ‘I am never interested in anything without love’.” The Trusted Eye, p. 140.

Peter Chametzky, University of South Carolina